Stevens Pass is located at an elevation of 4,061’ in the Cascade Mountains in Washington. The climate on the Pass is a maritime-influenced alpine subarctic climate that experiences short and mild summers and winters with extremely heavy snowfall. The Stevens Pass Ski Area is on Cowboy and Big Chief Mountains. The pass was named after John Frank Stevens, the first non-indigenous guy to discover it. In 1890, Stevens began a survey for the Great Northern Railway. He found the pass and decided that it would be a great place for the railway crossing and today, the BNSF’s Cascade Tunnel sits 1,180 feet below the summit of the pass.

On February 23, 1910 two Great Northern Railway trains were stalled on the tracks at the tunnel station due to big storms and avalanches. Six days later, on March 1, another avalanche came and swept both trains from the track, pushing them 150 feet down into the Tye River Valley and burying the train cars in a heap of snow and other debris. This catastrophic event, known as the Wellington Disaster, killed ninety-six people. Thirty-five of those deaths were passengers and the other sixty-one were railroad employees. This is considered the most deadly avalanche and one of the worst train accidents in the history of the United States.

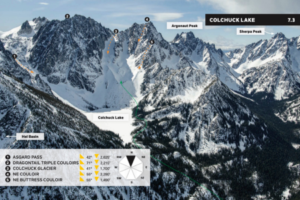

- Colchuck Lake descents from Beacon’s Washington’s East Side Stevens to Snoqualmie Pass Guidebook.

- Mount Stuart

- Probing

- Testing

- Stevens Pass Resort

Unfortunately, this is not the only deadly avalanche to have occurred on Stevens Pass. This area is prone to avalanches and is a zone that requires attention and caution. Over a century later in February of 2012, after three feet of fresh snow had fallen, a group of 16 experienced skiers were out in the backcountry in the Tunnel Creek area when an avalanche occurred and killed three of the men that were there that day.

Due to the dry snow and the high avalanche risk in this zone, we wanted to remind everyone how essential avalanche training is when you’re going to be in the backcountry.

The ski resort on Stevens Pass was started by two passionate skiers on Big Chief Mountain in the winter of 1937-1938. These two men had hauled an old V8 engine, some ropes and pulleys up the mountain to build their first rope tow. Aspiring skiers had to hike six miles in if coming from the west side or take a bus if coming from the east side. Skiers from Seattle to Wenatchee and even further came to ski the mountain. Popularity increased, and by 1963 the ski area had expanded to include twelve rope tows, the lodge, a shop, and three chairlifts. Eventually, they expanded into Mill Valley, which opened up terrain on three sides of both Big Chief and Cowboy Mountain.

Ownership of the resort has passed through many hands, and has finally landed on Vail Resorts as the current owners.

Parking on Hwy. 2 is an endangered species; it requires careful choices and planning to spot. Tunnel Creek is a no parking zone—and also an incredibly large terrain trap with a long history of accidents, as we’ve mentioned above. Parking at Stevens Pass is legal, but challenging due to its popularity and management’s lack of interest in supporting backcountry access as of this writing. Other parking on Hwy. 2 is variable and inconsistent. The Smithbrook parking lot is the only official spot to park, and even there, you may get plowed in. Follow the parking recommendations in the guidebook to decrease your chances of getting towed or plowed in.

There are some dangers and logistics to navigate in accessing this zone safely, but if done so, you’re in for a heck of a good time in some deep, fresh pow.