by todd | Jun 3, 2024 | World's Best Rock Climbing Areas

Buy Montmagny-L’Islet

La région de Montmagny-L’islet possède un excellent potentiel pour le développement de site de voies et de blocs. La région est bien située pour une grimpe rapide de la rive sud de Québec ou pour une pause escalade lors d’un long déplacement sur l’autoroute 20.

Le CEMA est fier de vous présenter le premier site officiel de la région. Le parc du rocher de la Chapelle situé au cœur du magnifique paysage rurale de Momtmagny est intéressant par sa proximité d’accès et d’approche. Le site est un beau laboratoire de mouvement de blocs et de voies. Il y a au rocher de la Chapelle, un peu de tout. On y trouve un beau mélange de problèmes de blocs, d’option pour faire de la moulinette et quelques belles voies sportives. Ce premier site dans la région pourra plaire à tous, de la petite famille aux grimpeurs d’expériences.

-

-

Nicolas Rodrigue on Retour aux Sources V3

-

-

Synthia Laurin on Pointe Lacaille 5.8

-

-

Nicolas Rodrigue on Ganesha V1

-

-

Synthia Laurin on Étole 5.9+

by todd | Nov 5, 2023 | World's Best Backcountry Skiing Areas

Buy Stevens Pass Guidebook

Stevens Pass is located at an elevation of 4,061’ in the Cascade Mountains in Washington. The climate on the Pass is a maritime-influenced alpine subarctic climate that experiences short and mild summers and winters with extremely heavy snowfall. The Stevens Pass Ski Area is on Cowboy and Big Chief Mountains. The pass was named after John Frank Stevens, the first non-indigenous guy to discover it. In 1890, Stevens began a survey for the Great Northern Railway. He found the pass and decided that it would be a great place for the railway crossing and today, the BNSF’s Cascade Tunnel sits 1,180 feet below the summit of the pass.

On February 23, 1910 two Great Northern Railway trains were stalled on the tracks at the tunnel station due to big storms and avalanches. Six days later, on March 1, another avalanche came and swept both trains from the track, pushing them 150 feet down into the Tye River Valley and burying the train cars in a heap of snow and other debris. This catastrophic event, known as the Wellington Disaster, killed ninety-six people. Thirty-five of those deaths were passengers and the other sixty-one were railroad employees. This is considered the most deadly avalanche and one of the worst train accidents in the history of the United States.

-

-

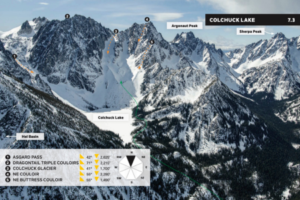

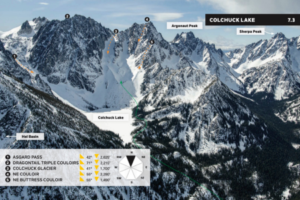

Colchuck Lake descents from Beacon’s Washington’s East Side Stevens to Snoqualmie Pass Guidebook.

-

-

Mount Stuart

-

-

Probing

-

-

Testing

-

-

Stevens Pass Resort

Unfortunately, this is not the only deadly avalanche to have occurred on Stevens Pass. This area is prone to avalanches and is a zone that requires attention and caution. Over a century later in February of 2012, after three feet of fresh snow had fallen, a group of 16 experienced skiers were out in the backcountry in the Tunnel Creek area when an avalanche occurred and killed three of the men that were there that day.

Due to the dry snow and the high avalanche risk in this zone, we wanted to remind everyone how essential avalanche training is when you’re going to be in the backcountry.

The ski resort on Stevens Pass was started by two passionate skiers on Big Chief Mountain in the winter of 1937-1938. These two men had hauled an old V8 engine, some ropes and pulleys up the mountain to build their first rope tow. Aspiring skiers had to hike six miles in if coming from the west side or take a bus if coming from the east side. Skiers from Seattle to Wenatchee and even further came to ski the mountain. Popularity increased, and by 1963 the ski area had expanded to include twelve rope tows, the lodge, a shop, and three chairlifts. Eventually, they expanded into Mill Valley, which opened up terrain on three sides of both Big Chief and Cowboy Mountain.

Ownership of the resort has passed through many hands, and has finally landed on Vail Resorts as the current owners.

Parking on Hwy. 2 is an endangered species; it requires careful choices and planning to spot. Tunnel Creek is a no parking zone—and also an incredibly large terrain trap with a long history of accidents, as we’ve mentioned above. Parking at Stevens Pass is legal, but challenging due to its popularity and management’s lack of interest in supporting backcountry access as of this writing. Other parking on Hwy. 2 is variable and inconsistent. The Smithbrook parking lot is the only official spot to park, and even there, you may get plowed in. Follow the parking recommendations in the guidebook to decrease your chances of getting towed or plowed in.

There are some dangers and logistics to navigate in accessing this zone safely, but if done so, you’re in for a heck of a good time in some deep, fresh pow.

Buy Stevens Pass Guidebook

by todd | Nov 5, 2023 | World's Best Backcountry Skiing Areas

Buy Taos and Santa Fe Guidebook

Being so far south in latitude and with nearly 300 sunny days a year, there’s a good chance you’ll be skiing in the sunshine in New Mexico. The snow here is unique because it is dry, cold, and powdery throughout the winter with great corn skiing in the spring. The snowpack also tends to be more consistent due to more minor temperature fluctuations than you are likely to see further north.

The Taos + Santa Fe guidebook can be divided into three geographical regions. The first is the Taos range that includes Wheeler Peak and the ski area there. The second region is the area around the Truchas Range, a lesser explored mountain. And lastly, Santa Fe and the mountain and sidecountry skiing there.

-

-

Ascending

-

-

Fresh turns, blue skies

-

-

Historical Wheeler Peak photo

The skiing history in New Mexico is rich and dates back to the late 1800s and early 1900s with prospectors trying out their skis for both practical uses and for casual fun. New Mexico is also home to what is likely the oldest-known photo of a Native American on skis. The image from around 1900, shows a man from Taos Pueblo on skis in Hondo Valley (just a few miles from Taos Ski Valley), holding one long wooden pole in lieu of the preferred two short ski poles of today.

With the advent of backcountry skiing technology, access has exploded and NM offers vast opportunities for the enthusiastic adventurer. This guidebook serves as a primer for what all is out there. There are even several abandoned ski resorts that serve as good places to ski. Generally, there is good freedom for backcountry access, but Taos Ski Valley is the exception. They don’t let you venture from the resort boundaries to out of bound terrain during the season. But, fun tip, you can ski inbounds once the resort is closed for the season because it is national forest land. The Taos Ski Valley can be found to the northwest of Wheeler Peak.

Wheeler Peak (13,167’) is the highest peak in the state of New Mexico. In the 1870s, U.S. Army Major George Montague Wheeler began to make a topographic map of the southwestern United States, and this included New Mexico. After climbing the peak, he named it after himself. In fact, at least six mountains in the southwestern US are named after him. He was likely not the first to summit Wheeler Peak, but it is believed that the people of the Taos Pueblo had likely climbed it for many years before a white man came to stand on top.

In northern New Mexico lies a brilliant turquoise body of water known as Blue Lake, or Ba Whyea, which is a sacred land to the native Taos Pueblos. This is because it is believed that they were born from the waters of the lake. The settling of Taos began in 1200- 1250 A.D. and it has been a place of worship and spiritual significance since that time.

In 1906, the US Congress grabbed that land from the native people and made it part of a national forest. For 64 years, protesting ensued. These people fought to get their land back, and finally, in 1970, around 48,000 acres of land, including the Blue Lake, was returned to the pueblo. Hurray!

From the Wheeler Peak East Fork Bowl, on top of Simpson Peak, you can see Blue Lake. Admire it from afar but don’t ski off the south side of Simpson towards it; it is a sensitive area that deserves respect. For more information, look in our guidebook.

Truchas Range

Truchas Peak, in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains is a north-south running massif with four discernible summits, North Truchas Peak, Middle Truchas Peak, “Medio Truchas Peak”, and South Truchas Peak. South Truchas is the highest of the four and it is considered to be the second highest peak in the state of New Mexico at 13,108’. It is also the most southerly peak in the continental United States to rise higher than 13,000’.

Truchas Range is one of the biggest backcountry ski endeavors in New Mexico because of the unpredictability and intrinsic remoteness in every direction. Skiing in this zone should not be underestimated; it is a high commitment zone that takes serious planning and preparation. SAR is far away, there is no avalanche forecast, no ski patrol, no cell phone coverage, no paved roads, no huts. You’re out there, and you get to experience a very real sense of wilderness.

It’s a big adventure with massive payoff because of the overall reward of being in such a pristine, massive wilderness area. You likely won’t see anyone else out there or even their tracks; it is relatively untouched.

One of the first developed ski areas in NM came in the 1930s at Hyde Park near Santa Fe.

In 1949, the Sierras de Santa Fe group founded the Santa Fe Ski Basin and raised funds to build its first chairlift. The 50s and 60s saw huge changes and major developments for resort skiing in the region and it has only continued to grow in popularity since.

Ski Santa Fe is located in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in northern New Mexico. It’s located in a beautiful alpine forest between 10,350’ (base) and 12,075’ (summit), which makes it one of the highest, and furthest south, ski resorts in the US.

Accessibility to Santa Fe is excellent during the winter season because you can take the lift at Ski Sante Fe to venture off into the backcountry and when you return, you can go back down through the resort. Check the Ski Santa Fe website for any updated rules and information. Backcountry skiing at Santa Fe is a bit more of a trek than in Taos, but not nearly as committing as the Truchas Range.

Whether you’re looking for an entirely remote destination like the Truchas Range, something full of other skiers like the Taos Range, or something in the middle like the Santa Fe Range, there’s a beautiful sunny slope waiting for you in New Mexico.

Buy Taos and Santa Fe Guidebook

by todd | Nov 5, 2023 | World's Best Backcountry Skiing Areas

Buy Marble Guidebook

During the 1960s and early 70s, developers obtained hundreds of acres of land with the intent of building a ski resort. They planned big, including 12 chairlifts, hotels, shops and restaurants. The plan bothered many of the local residents, so in an effort to keep Marble wild and secluded, they got together and in 1972 formed the Crystal Valley Environmental Protection Association. They had a goal of preventing the development of the Marble Ski Area and protecting the local environment as a whole. They had large hurdles to overcome, like the wealthy and powerful developers and bureaucrats who were more interested in profits than planet.

The project ran into issues; the land they had obtained was mostly south-facing and would get baked in the sun all day, there were hazards that prevented home sales, questions about the adequacy of water and sewage services, and a group of citizens that voiced their concerns whenever possible. The development plans never launched due to all of these troubles and allegations of illegal land sales. In the end, only one chairlift was ever built and it only operated for one season. The developers went bankrupt after two years, and the citizens’ group won that battle and has continued to fight for the environment and protect the Crystal River ever since. They are currently working on issues like the Coal Basin methane mitigation and helping find solutions to the overuse issues occurring from the off-road vehicles on the Lead King Loop.

-

-

Historic Colorado mine

-

-

Quarry Road approach

-

-

Marble Colorado

-

-

Quarry Road

Marble is known for its beauty in more ways than one. The Yule Marble Quarry is one of the biggest marble deposits known globally. It was founded in the 1870s and was the main source of profit for the town and it is still open today. Unlike most quarries, it is not an open pit mine; the marble deposits are found underground at 9,500’ of elevation, which means carving into steep mountainsides.

In 1941, operations stopped as there was no need for marble during the war, and since steel was in short supply, the mining equipment was stripped and sold off. The quarry reopened after 50 years, in 1990. Since then, ownership has changed hands many times. In 2010, Enrico Luciani bought the mine and began shipping marble to Italy, and to other countries in Europe and Asia. Today, it’s run by Colorado Stone Quarries.

Notably, the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. was built out of marble from this quarry in 1914. In 1931, Yule Quarry marble was used to construct the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery. A special type of marble called Calacatta Lincoln was first discovered in this quarry and is often considered to be the finest, in terms of both quality and purity, white marble on the planet.

To help keep Marble wild and with a heavy degree of solitude, we need to follow the rules in place that keep the businesses happy and keep everyone safe.

Let’s talk logistics. Parking and road access are important components to understand before booting up.

4WD or AWD is mandatory for driving the Quarry Road (County Road 3). Note that the road is narrow and mostly one lane, it is steep and can be slick from the snow and ice. Passing a quarry truck hauling marble is very difficult. To avoid this, stop at the quarry office at the beginning of the road to find out where the truck is. A pilot car precedes the truck on each run, if you see the car, they’ll ask you to pull over to let the truck pass, please do so.

The road crosses several avalanche paths, do not drive when the risk is high. There is zero opportunity for snowmobiling from Quarry Road. All terrain accessible from the road is considered advanced and has challenging avalanche terrain, there is nothing available here for beginners.

Buy Marble Guidebook

by todd | Nov 2, 2023 | World's Best Backcountry Skiing Areas

Buy Tahoe Guidebook

Lake Tahoe is the largest alpine lake in all of North America, sitting at an elevation of 6,225’. It is 22 miles long, has 75 miles of shoreline, and is 1,645 feet deep. It’s the second deepest lake in America, just after Crater Lake in Oregon which is 1,949 feet deep, and it is the 11th deepest lake in the world. The amount of water in the lake (39 trillion gallons) is enough to supply every person in the US with 50 gallons of water every day for five years.

The vibrant, turquoise blue waters of the lake get their color from the amount of algae present. The water is so clear that in some areas, objects can be seen at over 70 feet deep. One reason for the clarity, is that 40 percent of the precipitation falling on the Tahoe Lake Basin, falls directly onto the water. The rest of the precipitation is filtered through marshes and meadows before draining into the lake. Lake Tahoe is 99.994% pure water, making it one of the most pure bodies of water in the world.

-

-

Lake Tahoe

-

-

Skinning up

-

-

and up!

The lake gets its name from the Washoe Tribe of Native Americans that inhabited the lake for over 10,000 years. Tahoe means “big water” in Washo. Native Americans lived a somewhat secluded existence here until the lake was “found” by white men in 1844. The discovery went mostly unnoticed for years until Comstock Lode was found in Virginia City, Nevada. In the 1860s, Tahoe became a commercial hub because of the silver mines and railroads that were spreading out west. Because of the mining at Comstock, large-scale deforestation took place in the Tahoe Basin. The estimations of how much forest the Basin lost during this time are as high as 80%.

Over the next century, conservationists worked hard to protect Lake Tahoe. From 1912-1918, they tried to designate the Tahoe Basin as a national park, but they did not succeed. As pressures to develop the beautiful area increased in the 40s and 50s, a group was created called the League to Save Lake Tahoe in 1957. The League has been influential and imperative to the protection of the lake. They formed the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) which is a congressionally- approved agreement between California and Nevada to create environmental goals and take necessary actions to achieve and maintain those goals.

-

-

Granite patches on the approach.

-

-

Riding deep Tahoe pow!

We’ve talked a little about the history of the lake, but the story wouldn’t be complete without a discussion of the epic skiing that has taken place near the shores. It is said that the first people in the world to race competitively on skis were California gold miners. Miners started racing on skis during the Gold Rush in the early 1850s. The Lake Tahoe and Auburn ski clubs were early supporters and promoters of competition skiing. On Donner Summit, the Sugar Bowl was one of the first destination ski resorts in the country.

A man named Charles Nelson taught his friends how to ski in order to get around and have fun in the deep pow. He taught them how to make 7-12 foot long wooden boards that they shaped into skis and then sold for $6 in gold. The first legit, organized ski race championship in the world took place on February 15, 1867 in La Porte. The winner claimed a massive prize of $600.

In 1928, just a mile from the Tahoe Tavern at Lake Tahoe, an Olympic- size ski hill was built by a hired Norwegian man named Lars Haugen. Tryouts for the 1932 Winter Olympics were held here. The jump was named Granlibakken and was used and managed by the Lake Tahoe Ski Club.

The 30s brought huge changes as more and more people in the area began skiing and downhill or cross country racing competitively. The Southern Pacific Railway developed the Sugar Bowl, one of the first ski areas in the West. The 50s saw a dramatic increase in infrastructure that supported skiing and increased the number of people coming to the area. Today, people still flock to Tahoe to enjoy the sun and awesome pow. With crazy tours available around the state, it’s nice for there to be an option when the day calls for a light tour for one reason or another, that’s one thing that makes this book such a winner. The Light Tours of Lake Tahoe make for an incredible opportunity to explore some of the majestic wonder that this area has to offer.

For the Light Tours of Tahoe ski atlas, we identified many of the prime routes in this region that meet these criteria. For the places in our book where the skier might encounter a small, limited amount of avalanche terrain, we make a point to draw attention to it and describe it for the reader. Choosing to ski light tours doesn’t mean that you should venture out unprepared. It’s still paramount that you and your ski partners have avalanche training and are well equipped and knowledgeable.

Watching mounds of snow pile up on the ground can be exciting and intimidating for many backcountry enthusiasts. Many are eager to enjoy these spoils while they’re fresh, but the serious reality of avalanche risk can steer many away from journeying into the backcountry. The beauty of light tours is that they provide an alternative to your more challenging routes while still delivering delightful turns to those that are willing to sacrifice a greater rush of adrenaline for a lower risk option. Let’s say you’re looking to test out some of your new AT gear, or you’re heading out with a new ski partner, or a ton of fresh powder just fell and avalanche risk is high where you often ski; light tours serve as the perfect option for accomplishing any of these tasks. They may not suit the prototypical “instagram-worthy” experience that garners social media attention, but at the end of the day, no amount of likes is as valuable as one’s life.

Buy Tahoe Guidebook